An event stored in memory, on the other hand, can be revised without you knowing it--and is often not stored in its entirety. Instead, of an entire event being stored, often only a few bits and pieces of the original event make their way into memory.

So, why does it seem like you remembered the

whole thing when you only stored an incomplete outline of the event? Because

when you recall an event, you use what you know

about how the world works (i.e., your semantic memory) to turn that bare bones outline into a vivid memory

that seems complete. (See a 17-second

animation that gives you a general idea of what happens in

reconstruction)

Four amazing facts about reconstruction: the process of using your knowledge

of how the world works to take some bits of stored information to create a

"complete" memory.

- You don't realize that when you are reconstructing a memory you are not just copying what is already in memory. Instead, you may be writing much of your "memory" as you recall it.

- You are not very good at knowing which bits of your recall of an event are what you copied from what was originally written in memory and which bits you just made up. Your not knowing which part you made up makes makes sense given you didn't realize that you made up any of it. However, it creates a problem: As research on eyewitness testimony shows, there is little relationship between how sure you are about a memory and the memory's accuracy (As you will discover when you and your partner both claim to be 100% sure of correctly remembering a detail of an event, but you both remember it differently. Warning: When your partner says, "I know I'm right because I'm sure," pointing out that science shows that their being sure doesn't mean they're right may not help you win the argument.).

- You may continue to rewrite your memory every time you recall it, so memories may get revised without you knowing it. One implication: That 5-foot jump shot you made to win the game may, after telling the story numerous times, be remembered as a 15-foot jumper. Or, as basketball great Connie Hawkins said, "The older I get, the better I used to be."

- Memories are not copies of reality but instead are re-creations, so memories aren't as accurate as we would like to think (Examples of your memory's inaccuracy).

Experimental evidence for reconstruction

- Four-minute video summarizing one of the first experiments to demonstrate that memories can be reconstructed incorrectly false memory (I recommend muting the sound.)

- Watch a one-minute video about an experiment in which students were tricked into "remembering" seeing "Bugs Bunny" at Disney Land.

The bad news about reconstruction: Because memory, rather than being like a video recorder, relies on reconstruction, memories that we are confident about can be wrong. Examples:

- Eyewitness testimony is unreliable.

- False Memory Syndrome Foundation Website

- The End of Eyewitness Testimonies (Newsweek Article)

- Why science tells us not to rely on eyewitness accounts (Scientific American article)

- Innocent people falsely "remembering" being murderers (fascinating magazine article)

- Your first "memory" may be a false memory (short blog entry)

- Donald Trump reporting a false memory--or telling an awful lie.

- Donald Trump trying to use reconstruction to make some people "remember" that Americans couldn't say "Merry Christmas" during the Obama presidency.

- A memory error due to reconstruction may have cost Brian Williams millions of dollars.

- If you want to read a fascinating autobiography in which false memories play a role, borrow or buy Tara Westover's best selling book: "Educated."

- Sherlock Holmes never said, "Elementary, my dear Watson."; Captain Kirk never said "Beam me up, Scotty"; Shakespeare never wrote "A rose by any other name smells just as sweet"; Gandhi never said "Be the change you wish to see in the world"; and Tarzan never said "Me Tarzan, you Jane."

- Even people with phenomenal memories are not human tape-recorders. To see for yourself, judge how well the memory of a "human tape recorder" matches a transcript of an actual tape recorder (In this case, John Dean's testimony against President Nixon about a meeting that was secretly taped).

- Quotes to help you remember reconstruction's negative effects:

- It isn't so astonishing, the number of things that I can't remember, as the number of things I can remember that aren't so." --Josh Billings

- "I remember things the way they should have been."--Truman Capote

- "Memory is the great deceiver." --Neil Gaiman

- "Vanity plays lurid tricks with our memory" --Joseph Conrad

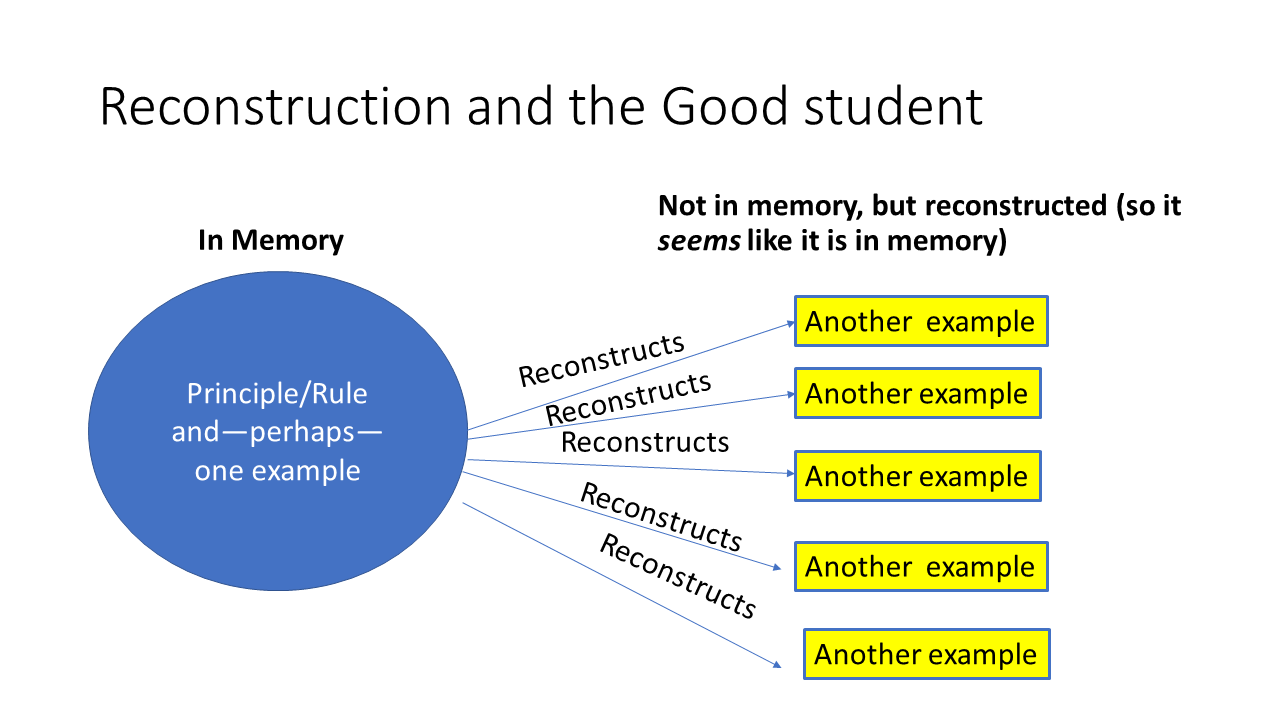

The good news about reconstruction: By noting what you can

reconstruct and memorizing only what you can't, it can seem like you

have remembered everything without memorizing much.

If visuals help you,

mouse over this text.

So, oddly enough, the key to seeming like you have memorized more is to memorize less! For example, imagine that a friend tries to memorize every word of a 30-page chapter whereas you boil down that chapter to less than a page of notes from which you can reconstruct the chapter. You will memorize less than a page of notes but appear to know much more than your friend. But can you really summarize an entire chapter in one page of notes? Yes. In fact, one highly paid memory expert advises his clients to end the semester with one page of notes for each course!

How do you boil down a long chapter to less than one page of notes?

- Preview the chapter so you are ready to ask

- Which information in the chapter can you reconstruct from what you already know?

- What are the main points from which you can reconstruct the rest of the chapter?

- Keep in mind that you should be able to reconstruct most of the chapter, so either do not highlight anything--take notes instead--or highlight only the most important information on the page and go back later to try to reconstruct the rest of the page from the few words you highlighted. (Students who use highlighters to paint their books are obviously not being selective and thus are not taking advantage of reconstruction.)

- Realize that condensing a chapter down to less than one page of notes may not happen in one step. You may have to rewrite your summary several times, shortening it by (1) eliminating material in the previous summary that is either redundant (e.g., two examples of the same thing) or material that you could reconstruct and (2) replacing relatively narrow principles with broader principles.